Categories

Have you ever been in any of these situations?

⇒ You have a stable child who just needs fluids, but no laboratory tests

⇒ You’ve tried PO hydration, to no avail, despite anti-emetics

⇒ You’re poking the stable, but dehydrated child repeatedly without success

What now?

Hypodermoclysis, otherwise known as subcutaneous rehydration.

[Insert Player]

Clysis comes from the same Greek word that “a flood” – hypodermoclysis refers to flooding the subcutaneous space with fluid, so that it can be absorbed systemically.

Sound far-fetched?

Well, it turns out, what is old is new again.

In 1913, Dr Day first described this technique for a child with severe diarrhea who could not tolerate fluids by mouth. Hypodermoclysis then began to gain popularity with a peak of use in the 1940s, until an innovative breakthrough in 1950. Dr David Massa, a resident anesthesiologist at the Mayo clinic, invented the first catheter-over-needle apparatus.

With increasing safety and ready access of IV catheters, IV quickly overshadowed SC.

The subcutaneous route of hydration has also been used effectively in geriatric and palliative care for decades, and it is only now beginning to gain popularity again in its original population: children.

So, how does it work?

In a nutshell, you place a butterfly needle or angiocatheter in the subcutaneous space and you run fluids into it. The tissues quickly absorb the fluids, making them available systemically. That’s it. Everything else is just finesse.

The ideal candidate for hypodermoclysis is the stable patient, with mild to moderate dehydration who fails a trial of fluids by mouth, or who needs a bridge to gaining IV access later, after a slow subcutaneous fluid bolus is given.

Ok, so how do you do it?

Place a topical anesthetic cream, such as EMLA, cover with occlusive dressing (IV dressing), wait 15-20 min

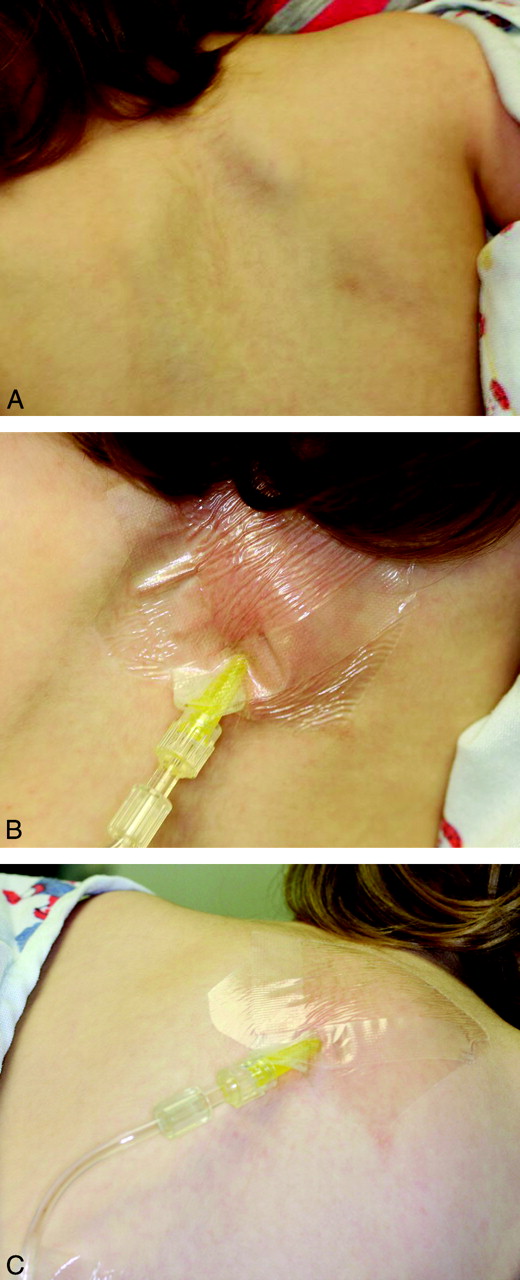

"Pinch an inch" of skin anywhere, but the most practical site in young children is between the scapulae

Insert a 25-gauge butterfly needle or 24-gauge angiocatheter (preferred by the author), secure

Inject 150 U hyaluronidase SC, if available

Infuse 20 mL/kg isotonic solution over one hour, repeat as needed or use "bolus" as bridge to IV access

You can set the line to gravity, and if it is dripping in, you may leave it be. If you see a very slow drip by gravity, or worse, nothing is dripping, you can set the line on a pump, to deliver up to 20 mL/kg over an hour. Infusion at this rate optimizes the balance we want in minimal discomfort while maximizing the flow rate.

This is not a “bolus” in the true sense – but then, when you compare it to the alternative – like IV therapy – and we see a time and cost savings. Dr Mace and colleagues in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine report substantially decreased cost and ED length of stay when comparing the material and human resources needed to place an IV in a squirmy young child, compared with a simple subcutaneous stick.

There will be swelling

There will be swelling – that is the goal. It is really painless, and your patient may lie down on his back with the pump going – it is actually pretty comfortable for most children and adults to do.

Here’s a tip – since there will be swelling, we want to be careful about how we secure the line, so how you tape it down to the skin is important – we want to avoid a pulling sensation, which can be the beginning of the end of the tolerance for the procedure. Cover that with an occlusive dressing, as you would an IV site. The footprint of the occlusive dressing is relatively small, so it will travel up on top of the subcutaneous mound you’re creating. As the line exits the occlusive patch, place a thin layer of gauze between the skin and the IV tubing, so that the tubing doesn’t press into the skin. Then—as far away from the puncture site as possible—tape it down securely. The idea is not to tape on the growing mound itself, because the mound may pull at the anchored skin and set a nuclear chain reaction of annoyance and restlessness – and potentially a failed procedure.

Here’s a tip – since there will be swelling, we want to be careful about how we secure the line, so how you tape it down to the skin is important – we want to avoid a pulling sensation, which can be the beginning of the end of the tolerance for the procedure. Cover that with an occlusive dressing, as you would an IV site. The footprint of the occlusive dressing is relatively small, so it will travel up on top of the subcutaneous mound you’re creating. As the line exits the occlusive patch, place a thin layer of gauze between the skin and the IV tubing, so that the tubing doesn’t press into the skin. Then—as far away from the puncture site as possible—tape it down securely. The idea is not to tape on the growing mound itself, because the mound may pull at the anchored skin and set a nuclear chain reaction of annoyance and restlessness – and potentially a failed procedure.

The swelling will look indurated, a pinkish red. It’s not an allergic reaction: even with the old preparations of hyaluronidase, allergic reactions were rare, and now they are very rare with the recombinant preparation. It is supposed to swell and look ugly. The subcutaneous tissues will swell to a point where you have a steady state fluid administration rate, and as soon as you stop the infusion, the remaining fluid will start to subside as it is absorbed.

A Bridge to IV Therapy?

Kuensting et al. in the Journal of Emergency Nursing in 2013 compared subcutaneous fluid infusion with intravenous fluid infusion in children with difficult IV access. They found the mean time from order entry to subcutaneous fluid infusion to be 20 min, compared to the failed IV access group with an average infusion start time of 1.5 hours. The latter group eventually received subcutaneous fluids. The investigators also found a shorter ED length of stay in the subcutaneous group.

In the same study, a subgroup received subcutaneous fluids initially, and later an IV. They found a trend in ease of IV access after subcutaneous fluid therapy. In other words, if your little patient with difficult IV access is hemodynamically stable and amenable to a bolus over an hour, you may choose to start with hypodermoclysis and reevaluate.

Predicting Difficult IV Access in Children

Much has been studied and written about the predictors of difficult IV access in children. The most often cited are: age < 3 years, weight less than 5 kg, prematurity, obesity, and darker skin tones, where the contrast of vein to skin may not be so apparent.

The three main predictors of the score validated by Riker et al. in Annals of Emergency Medicine include the most practical and universal of features: vein palpability, vein visibility, and patient age.

If you’re anticipating difficult IV access in the child who can stand to wait an hour for a slow bolus, you may start with the subcutaneous route to get those veins plumper and more visible, to improve your chances of IV access in the very near future.

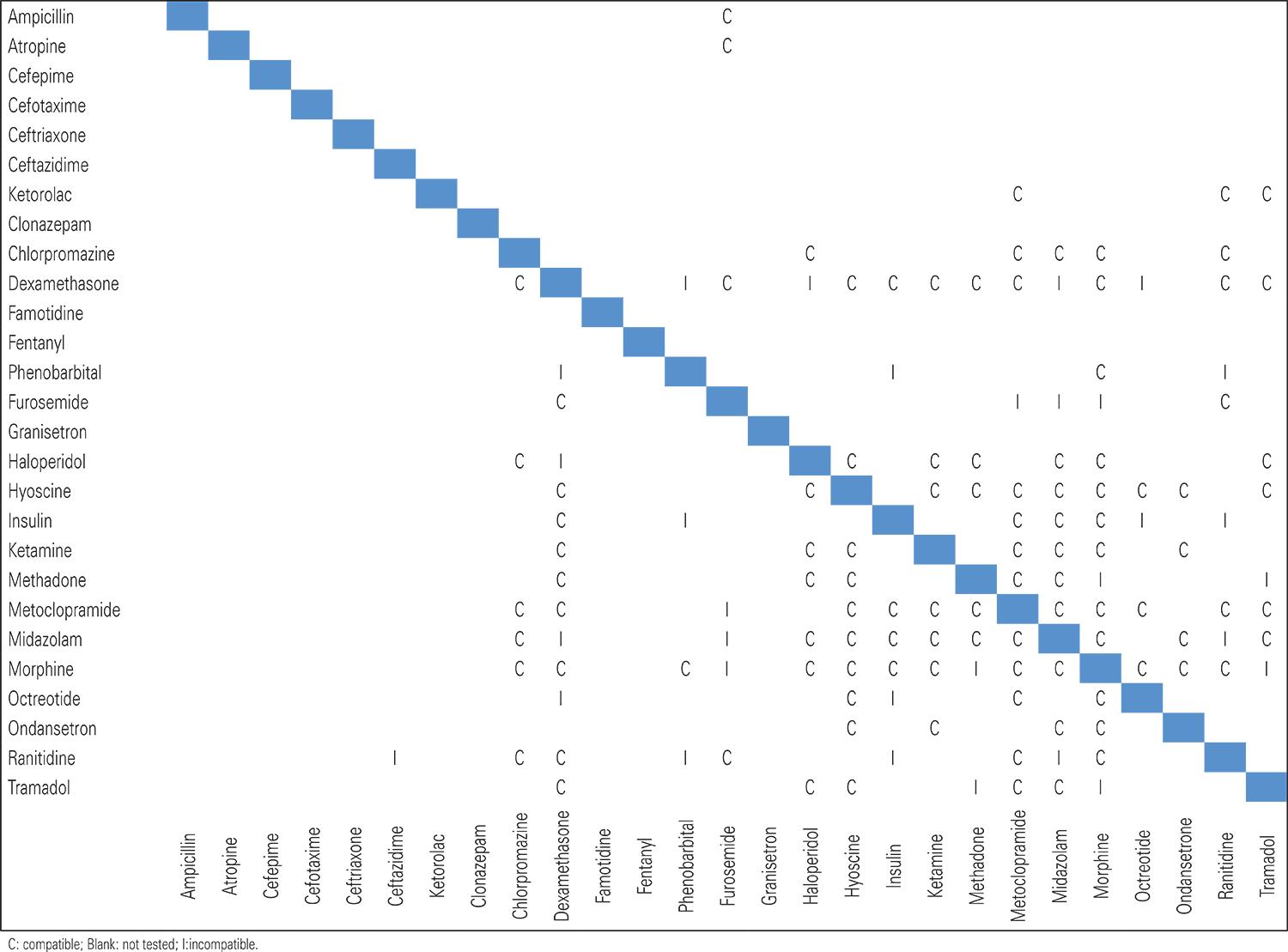

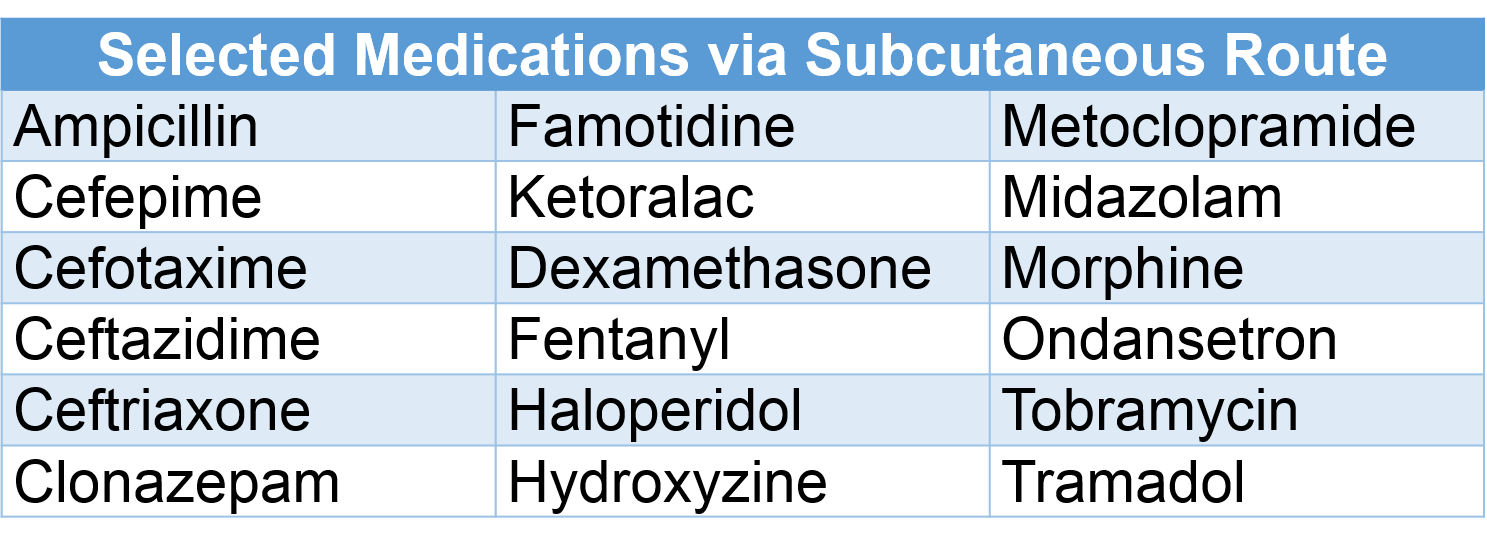

Medications via Subcutaneous Route

Certain medications have been used safely via subcutaneous infusion; always check dose, rate, and compatibility.

What about catheter size?

You don’t need to use larger needles or angiocathters for older children, adolescents or adults. A 25-gauge butterfly or 24-gauge angiocatheter works well from an infant to an elder. In one study of adults, a half a liter of saline was infused by gravity via a 24-gauge catheter. With IVs, the shorter and larger the bore, the faster the infusion.

In subcutaneous infusion, it is not the size of the catheter, but the osmotic gradient that determines the rate of absorption.

What if I don't have that fancy hyaluronidase?

It’s actually increasingly readily found – and available in generic form. If you have it, please use it – it will make a believer out of you and others.

Hypodermoclysis will work without hyaluronidase – the process of subcutaneous rehydration just takes a lot longer to work. In a double-blind cross-over trial Thomas et al. in 2007 compared subcutaneous administration of lactated ringer’s solution by gravity with and without hyalurondase. The hyaluronidase group received their fluids 5 times faster. The average rate of the hyaluronidase group was 382 mL/h versus the fluid only group, who did not receive hyalurinodase; they were substantially slower, at 82 mL/h. It’s worth using if you have it, but still potentially useful if you don’t.

Recap: Supplies

√ EMLA or any topical anesthetic used for intact skin, placed as soon as the decision is made

√ A 25-gauge butterfly needle or 24-gauge angiocatheter

√ IV tubing, gauze to pad, tape to anchor

√ 150 U hyaluronidase, the same dose, regardless of age or size

√ Isotonic fluids – you can start with 20 ml/kg

√ And finally a well informed team made up by the patient, the parents, and your staff, so that everyone knows what to expect for a successful subcutaneous fluid administration.

References

Smith LS. Hypodermoclysis with older adults. Nursing. 2014 Dec;44(12):66.

This post and podcast are dedicated to Christina L. Shenvi, MD, PhD, for her dedication to excellence in patient care and enthusiasm in #FOAMed, Emergency Medicine, and Geriatric Emergency Medicine. There are many shared lessons learned in the care of children, elders, and families. Thank you.

Catch Dr Shenvi on the innovative GEMcast.

Subcutaneous Infusion

Powered by #FOAMed -- Tim Horeczko, MD, MSCR, FACEP, FAAP