Categories

Blood in the vomit.

Blood in the stool.

Blood in the diaper.

How far do I go in my investigation?

What do I really have to worry about?

The differential diagnosis of GI bleeding in children is broad.

(Here is the complete differential diagnosis)

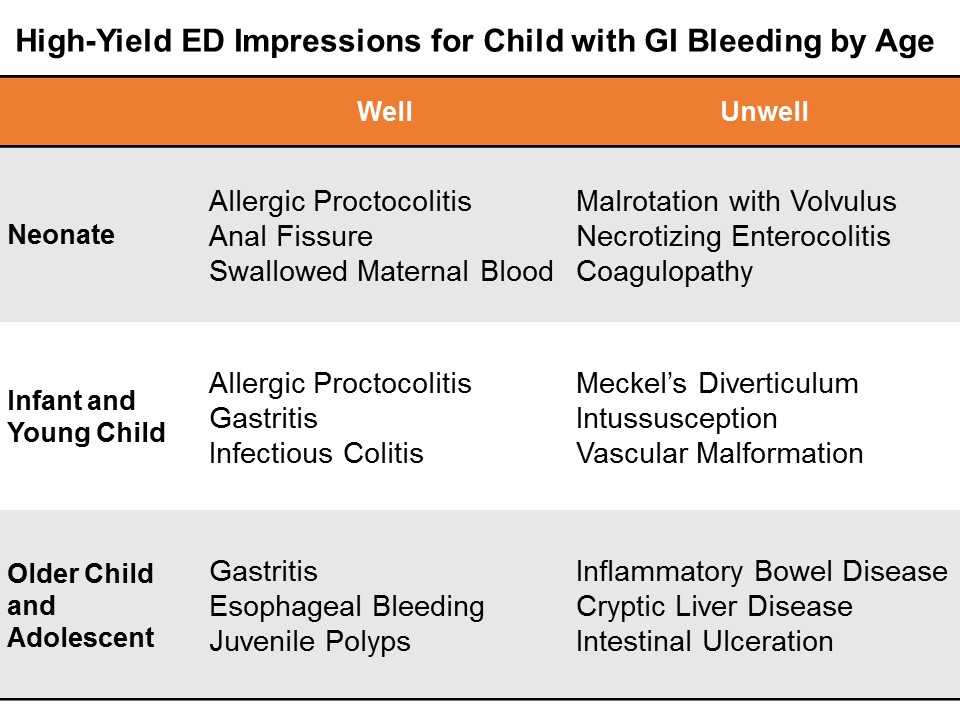

In the ED, we can simplify by categorizing by age and appearance.

Neonates

GI bleeding in the neonate (less than one month of age) is serious until proven otherwise.

Well appearing?

If this in obvious anal fissure, then no further work-up is necessary. Counsel on proper feeding and follow-up.

Evaluate for potential swallowed maternal blood by examining mother with a chaperone, then perform the Apt test.

Consider allergic proctocolitis if the child is well. Counsel the breastfeeding mother on diet modification. If formula fed, the child should feed through thus until the primary care physician decides whether to start the sticky process of changing up formulas.

If unclear, consider a complete blood count and/or further work-up and admission if unwell.

Ill Appearing?

The three most dangerous diagnoses in the neonate are necrotizing enterocolitis, malrotation with volvulus, and inherited coagulopathy. It is important to note that 15% of necrotizing enterocolitis occurs in full-term babies; malrotation can present simply in shock, without initial overt bleed. Inherited conditions may not be known to the family early on, as they have not yet heard back from the neonatal screening done at birth.

Pitfalls in the neonate and infant

Genitourinary bleeding; hematuria; or uric acid crystals: the classic fake out here is the orange or pink stained diaper – that is actually residue from deposits of uric acid crystals in the urine, an almost always benign phenomenon in which the concentrated crystals oxidize and stain the diaper, frightening the parents.

Think -- pink stain, without clot:

Infants and Young Children

Well appearing?

Through the first year to age 5, things like infectious colitis and gastritis are common.

Ill appearing?

Think about intussusception, cryptic liver disease, or esophageal bleeding. Check the skin – is that a dark purple palpable rash on the buttocks? Think Henoch-Schoenlein purpura.

Focus: Meckel's Diverticulum

Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital malformation of the GI tract, and the most common cause of GI bleeding in the toddler. It is a remnant of the omphalomesenteric tract – it came from a long tube that once connected the yolk sac to the lumen of the midgut. A stranded island of gastric tissue secretes acid in the intestine, where it doesn’t belong. Sometimes these islands never cause much trouble.

When it does present itself, a Meckel’s diverticulum usually follows the rule of twos:

Presents by age 2

Affects 2% of the population

Often 2 inches in length

May include 2 types of mucosa

Found within 2 feet of the ileocecal valve.

Not actively bleeding: technetium-99 pertechnate scintigram (Meckel’s scan).

Actively bleeding: radio-labeled red blood-cell scan (resuscitate and call your surgeons!)

Pitfalls in the infant and young child

Epistaxis; food-related misadventures

Older Child and Adolescent

Well appearing?

Mallory-Weiss tears after forceful vomiting; trivial hemoptysis after viral symptoms; pill esophagitis in the child is just learning to swallow medications. Always consider foreign body ingestion.

Ill Appearing?

Varices from cryptic liver disease; hemorrhagic gastritis; vascular malformation, such as a Dieulafoy lesion, where a tortuous small artery ends just superficial to the gastric mucosa, and can erode through and erupt.

Focus: Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Approximately a quarter of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) -- both Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn disease – will present by age 20. Children and adolescents may present with the classic symptoms of IBD: abdominal pain, weight loss, bloody diarrhea, but many present atypically with isolated signs like poor growth, anemia, or delayed puberty.

You may also suspect IBD in the child with other extra-intestinal symptoms like oral ulcers, clubbing, erythema nodosum, jaundice, or hepatomegaly.

On history and physical examination, you may get one of three cardinal presentations

Fatigue, history of anemia, in a stable child who comes to the ED with bloody diarrhea

Chronic diarrhea, chronic abdominal pain, and poor weight gain or weight loss

A fulminant presentation, with severe abdominal pain, frankly bloody stools, tenesmus, fever, leukocytosis, and hypoalbuminemia.

On exam, look for general appearance, glossitis from B2 deficiency, hair loss and brittle nails form protein loss, purpura (from vitamin C and vitamin K deficiencies). Look for evidence of episcleritis or uveitis. Listen for rubs as in pericarditis. Do a good abdominal exam, especially looking for hepatomegaly. Perirectal skin tags are not uncommon. Children with IBD may form urinary calculi form oxalate crystal deposition. Do a thorough skin and neurologic exam.

Treatment for both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease is similar.

Induction therapy: children with mild disease get aminosalicylates; those with moderate disease get steroids; and those with severe disease get cyclosporine.

Maintenance regimens to prevent relapse include aminosalicylates, mercaptopurine, and azathioprine.

Surgical treatments for refractory colitis include an ileal pouch and anal anastomosis – also called a J pouch, a type of neorectum created surgically by folding loops of ileum back on themselves and stitching them together to create a larger rectal reservoir where the rectum once was. A neorectum allows the child to have voluntary control of his stools again.

Stabilizing the Pediatric GI Bleed

Life-threatening GI bleeding in children is, thankfully, rare, but we have to be prepared.

Give blood for compensated shock, prepare for massive transfusion if giving more than 40 mL/kg total blood products.

Differing Etiologies: adults and children

The reasons for upper GI bleed in adults are vastly different from those of children. In adults, mostly the life-threats are due to liver disease, varices, or hemorrhagic gastritis.

In children, critical upper GI bleed is often secondary to critical illness (hemorrhagic gastritis or stress ulcer), or vascular malformation. Critical lower gastrointestinal bleeding may be from Meckel's diverticulum or other congenital angiodysplasia.

Endoscopy

Get your patient urgent endoscopy as soon as possible after arrival if there is active bleeding. Otherwise, according to the Belgian guidelines, stable children may have endoscopy within the first 24 hours of hospitalization. The reported efficacy of endoscopy for controlling upper GI bleeding in children is approximately 90%.

Miscellaneous

Nasogastric tube? No routine role (unreliable to rule out or stratify upper GI bleed).

Proton pump inhibitor? No good data, but no major common contraindications.

Octreotide, vasopressin, broad-spectrum antibiotics? May use adult data to extrapolate in the proper etiologic context.

General Advice for the Brisk GI Bleed in Children

This is a rare, but potentially life threatening situation, so anticipate how the child can decline, and get your team assembled: your pediatric intensivist, gastroenterologist, and surgeon – especially if we can’t ge the upper GI bleed to abate with endoscopy. The sooner you activate the team, the better.

Summary

The broad differential diagnosis may be paralyzing, and frustrating, since much of it we cannot discern in the ED.

Consider actionable, high-yield etiologies based on age and appearance.

Neonates

Well appearing? Think rectal fissure, maternal blood, or allergic proctocolitis

Ill appearing? Think necrotizing enterocolitis, malrotation, or an inherited coagulaopathy.

Infants, and Young Children

Well appearing? Think infectious colitis and gastritis.

Ill appearing? Think intussusception and Meckel’s diverticulum.

Older Children and Adolescents

Well appearing? Think Mallory Weiss tear from vomiting, or gastritis

Ill appearing? Think metabolic, cryptic liver disease, or inflammatory bowel disease.

For everyone – a careful history and a good physical exam will point you tto the etiology, or risk-stratify for further outpatient evaluation and management.

References

This post and podcast are dedicated to Carlo D'Apuzzo, MD for his creativity, innovation, and dedication to the highest standards of emergency care. Le tue pillole sono buona medicina. Grazie, Carlo per tutto quello che fai per il mondo #FOAMed.

Powered by #FOAMed -- Tim Horeczko, MD, MSCR, FACEP, FAAP