Categories

Johnny has fallen on an outstretched hand, and comes to you with a swollen, painful elbow.

Position of comfort, analgesia, xrays, and now what?

What am I seeing -- or not seeing -- here?

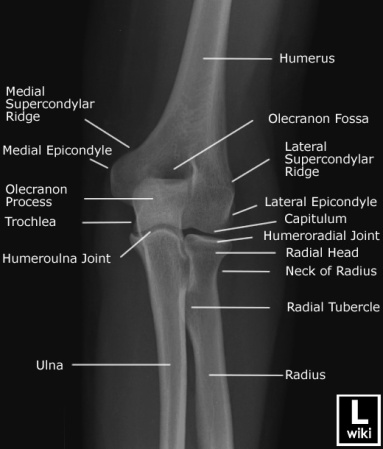

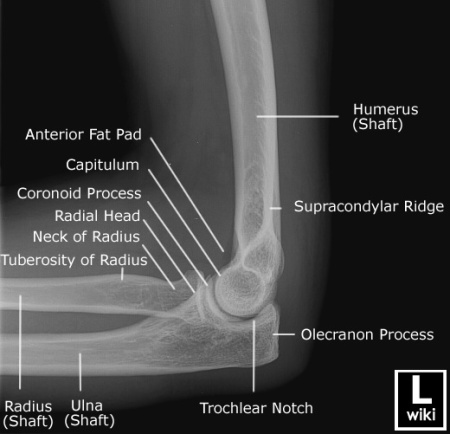

First a refresher on radiographic anatomy of the elbow --

Images courtesy of Radioglypics (Open Access Radiology Education). Used with permission.

Now that we have our adult anatomy reviewed, let's go through the development of the elbow in a child.

We are all born with primary ossification centers -- the basic shapes of our long bones. Secondary ossification centers then develop around the ends of our long bones, and make interpretation of films in the context of suspected injury difficult.

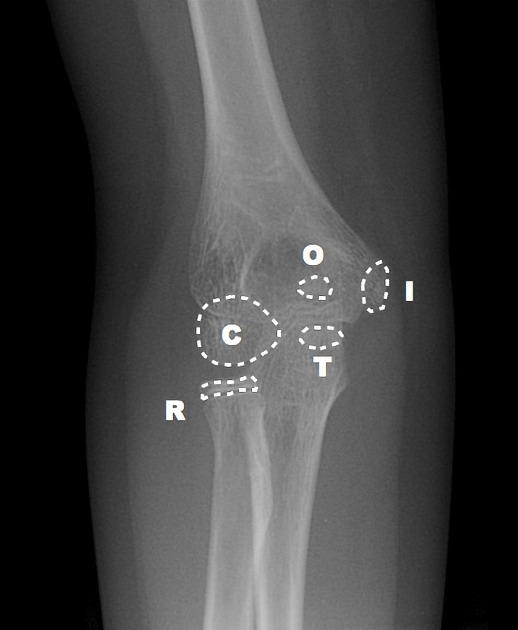

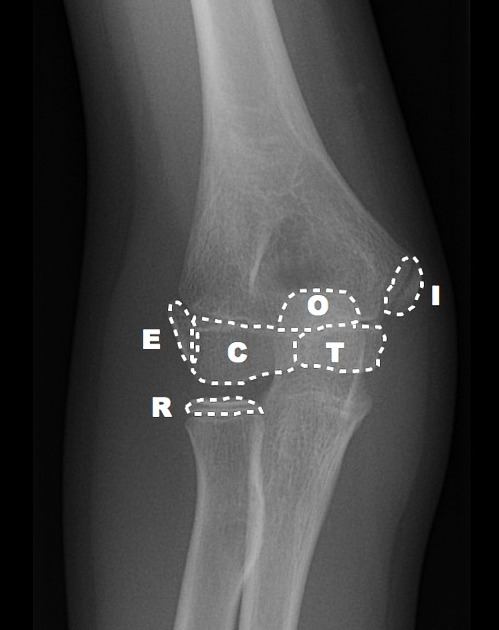

Elbow Interpretation Roadmap: CRITOE

More pragmatic and utilitarian than a prosaic mnemonic, CRITOE helps us to remember the order of ossification of the pediatric elbow.

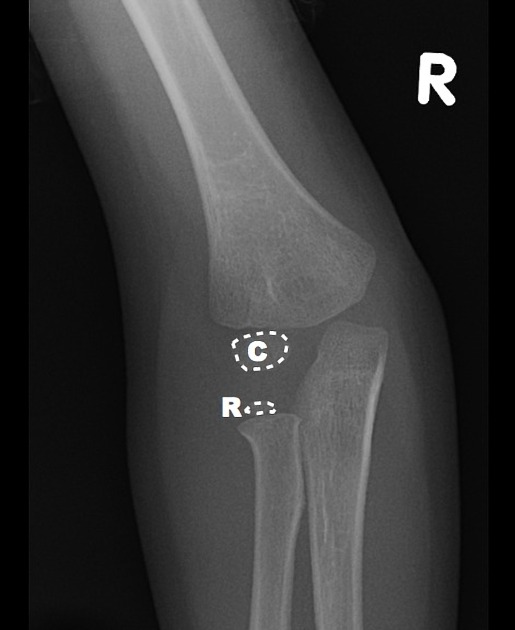

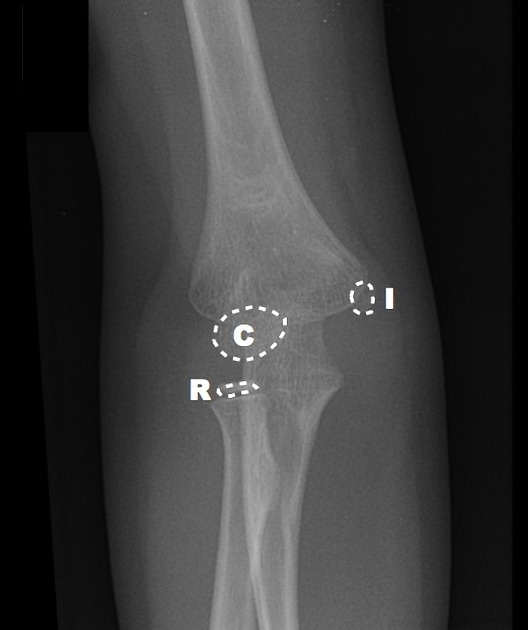

Although children develop at different rates, the order of ossification is programmed into us. Images courtesy of Radiopaedia.

Capitellum

By age one, the capitellum ossifies. On the AP view, imagine a little white oval balloon floating in the darkness between the radius and the humerus.

Radial Head

By age three, the capitellum gets another little balloon to join the party. The radial head is a bony little balloon that floats just above the floor. If you see both little balloons floating on either ends of the space between the humerus and the radius – you know this child is about three years old.

Internal Epicondyle

By the age of five, the capitellum and radial head are no longer little floating balloons, but now taking on shapes that resemble what they will look like as an adult. By age five, you’ve grown out of balloons, and have moved on to Frisbees. The internal epicondyle (meaning the medial epicondyle) starts to ossify by age five – a little bony Frisbee.

Trochlea

By age seven, another little Frisbee flies around. On the AP view, the trochlea is superimposed on the humerus – if you look at the distal medial humerus, you’ll see the trochlea like a little oval Frisbee taking shape (see combined film below).

Olecranon

By age nine, the olecranon of the ulna is ossifying. In a nine year old, you’ll see a capitellum, radial head, internal epicondyle, trochlea, and olecranon.

External Epidondyle

By age 11, you start to ossify your external epicondyle (lateral epicondyle).

Pediatric Elbow Films: Putting It All Together

Watch this dynamic video by Dr Jeremy Jones from Radiopaedia:

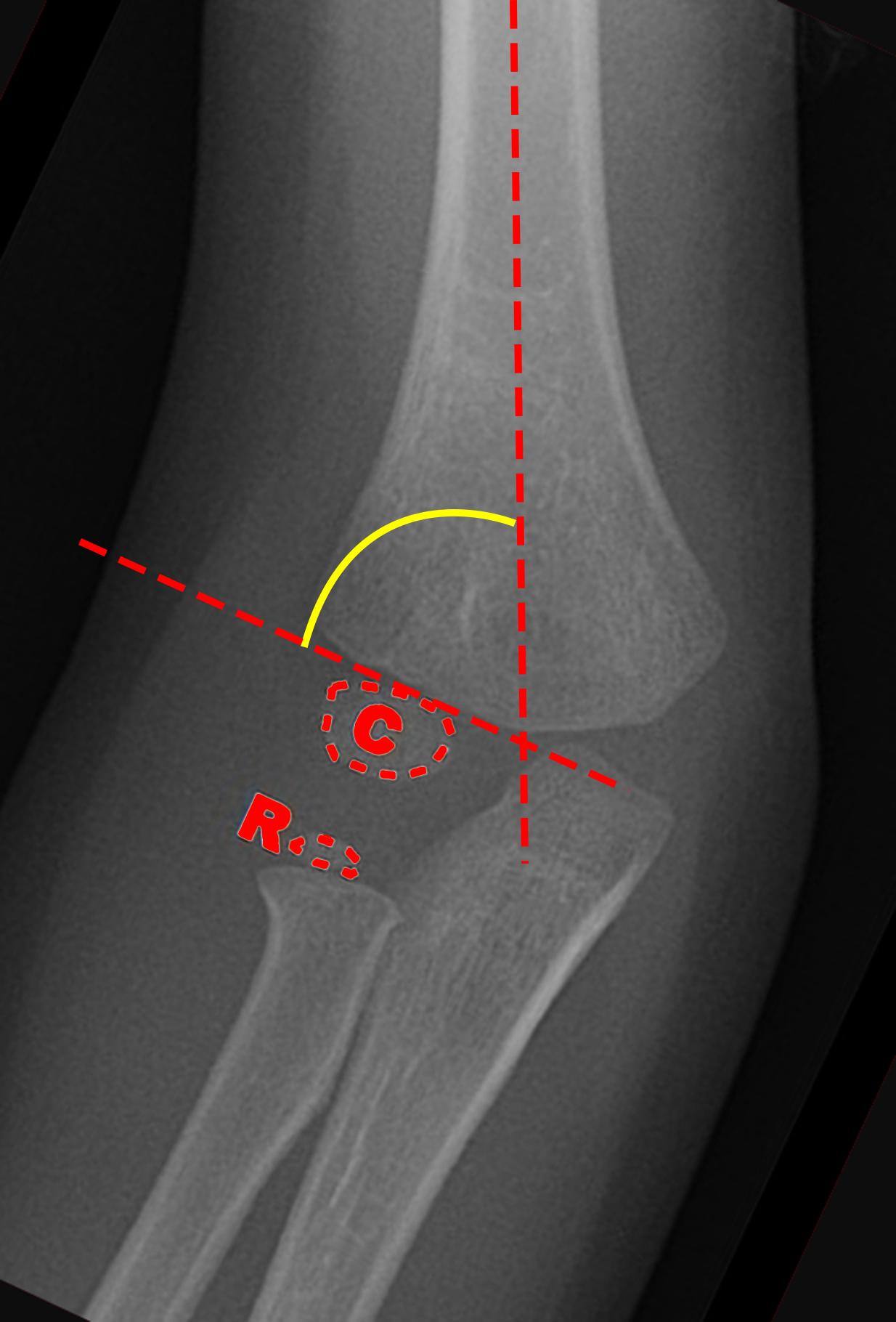

Fracture Saviors: Fat Pads and Drawn Lines

These three things can save us: fat pads, the anterior humeral line, and the radiocapitellar line. Non-annotated images courtesy of Heidi Nunn.

Normal anterior fat pad

Sail sign: billowing hypodensity, indicating blood; sometimes the only (indirect) sign of an elbow fracture

Posterior fat pad: always pathologic

Radiocapitellar Line: anterior humeral line bisects the capitellum

Baumann’s angle (carrying angle): Normal is 70 to 75 degrees. A difference between extremities of just 5 degrees or more is abnormal.

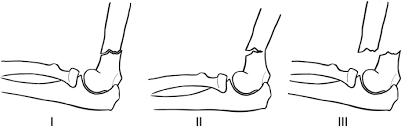

Supracondylar fractures: Gartland Classification

Compartment Syndrome

Pain out of proportion to exam, paresthesias, pallor, poikilothermia, pulselessness, and paralysis

The 6 Ps of compartment syndrome are not sensitive in children.

The only thing that may alert you to increasing compartment pressures in children is an increasing need for analgesics.

Volkmann's ischemic contracture

Untreated compartment syndrome results in thrombosis, edema, ischemia, and disabling contracture.

Other Elbow Injuries

(Details in podcast audio)

Lateral Condyle Fracture

Medial Epicondyle Fracture

Radial head and radial neck fractures

Olecranon fractures

Elbow dislocation

Radial head subluxation (nursemaid’s elbow)

Medial epicondylar apophysitis (Little leager’s elbow)

Test your retention: check out this interactive post from the team at Don't Forget the Bubbles.

Key Points and Summary

The most important pediatric elbow injury is the supracondylar fracture. Grade I is minimally displaced and needs a cast; Grade II is displaced, but with the posterior cortex intact; after closed reduction, the child may still need surgery; Grade III fractures all need closed reduction, internal fixation, and close monitoring for compartment syndrome.

CRITOE gives us the order of ossification for the pediatric elbow – capitellum, radial head, internal epicondyle, trochlea, external epicondyle, and olecranon -- typically occurring at year 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 – remember the order is the most important thing – all ossification centers should be accounted for. Make sure one is not missing – or where one has been “created” traumatically.

If you don't see the obvious fracture, you can be "saved" by the sail sign and/or a posterior fat pad. Also, make sure to look for the anterior humeral line – on the lateral view, a line drawn down the anterior humerus – if it intersects with the middle third of the capitellum, that is normal – it not, suspect a supracondylar fracture.

The radiocapetellar line runs along the radial neck through the radial head and should line up nicely with the capitellum. If not, assume a fracture-dislocation.

Close communication and coordination with the orthopedist will help us to get the right care at the right time – there is some variability with orthopedic practice, so be open to that – we can make out biggest impact by making the right diagnosis, and aggressively treating pain and effectively providing procedural sedation when needed.

References

Bonus! Watch Larry Mellick Reduce a Nursemaid's Elbow!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-0ROu4hCXwQ

This post and podcast are dedicated to Andy Neill, MBBS. Thank you for your humanism and your dogged dedication to connect with the learner and simplify complex concepts. Welcome back, Andy!

Powered by #FOAMed -- Tim Horeczko, MD, MSCR, FACEP, FAAP